Marcel Pardo Ariza (they/he) is a trans, Colombian, visual artist, educator, and curator based in Oakland/San Francisco. Their interdisciplinary practice spans constructed photography, site-specific installations, and collective public programming, centering care, trans history, and the magic of queer nightlife. Marcel’s recent time at the Fire Island Artist Residency (FIAR) offered a space to engage deeply with the island’s layered queer histories while developing projects that foreground kinship, visibility, and joy.

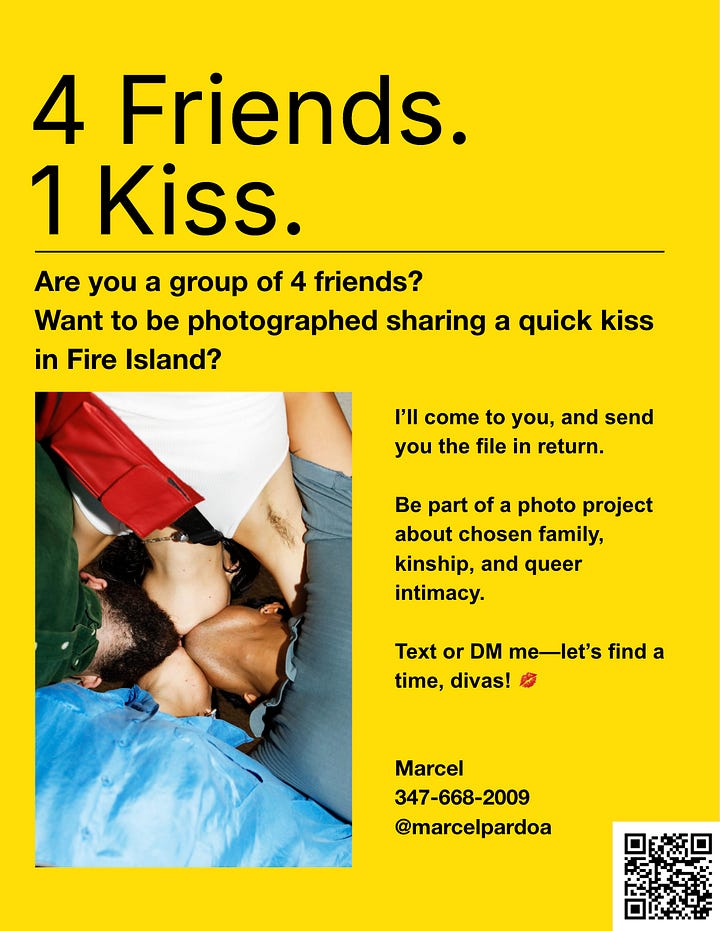

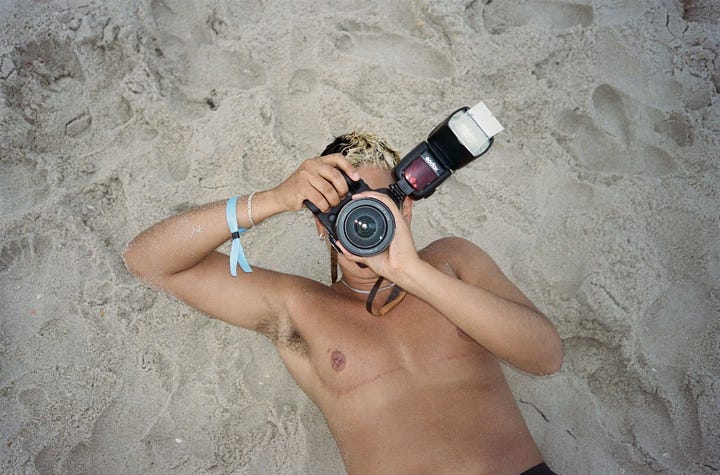

During the residency, Marcel invited participants to take part in 4 Friends 1 Kiss, photographing groups of friends kissing from below, a project that both activated the FIAR community and explored the ways intimacy and play can resist the political and social violences of our time. Their work reflects a commitment to creating spaces of reciprocity and care, while also responding to the historic absences of trans Latinx narratives in visual culture.

What does it mean to be queer for you in 2025?

For me, being queer today means upholding and protecting the rights that we, and those before us, have fought so fiercely for. There are so many layers to this. As a trans migrant, I focus on defending trans rights, gender-affirming health care, and immigrants’ rights, while also teaching my students and young people about trans history and the importance of intergenerational connections. I see queerness not only as an identity, but also as a responsibility to care for our communities and to make sure that the paths ahead are wider and safer for those who come next.

Queerness for me is also about cultivating connections and spaces that foster joy, reciprocity, and dancing. Dancing, always the best balm!!

How did your work manifest during your time at FIAR? What did you work on?

I came to FIAR with lots of ideas, but I wanted the island to influence how I spent my time there. Considering the island’s historical significance in queer history and kinship, I decided to invite people to participate in my project, “4 Friends 1 Kiss.” In it, I photograph groups of four friends kissing, taken from below.

We’re living through such violent political times, and I always turn to the importance of friendship and kinship, a well that can sweetly nurture the heart and soul. This felt like the right project for the island, a way to meet new people and connect with them. I made posters and hung them all around Cherry Grove and The Pines, inviting anyone who would be down to participate.

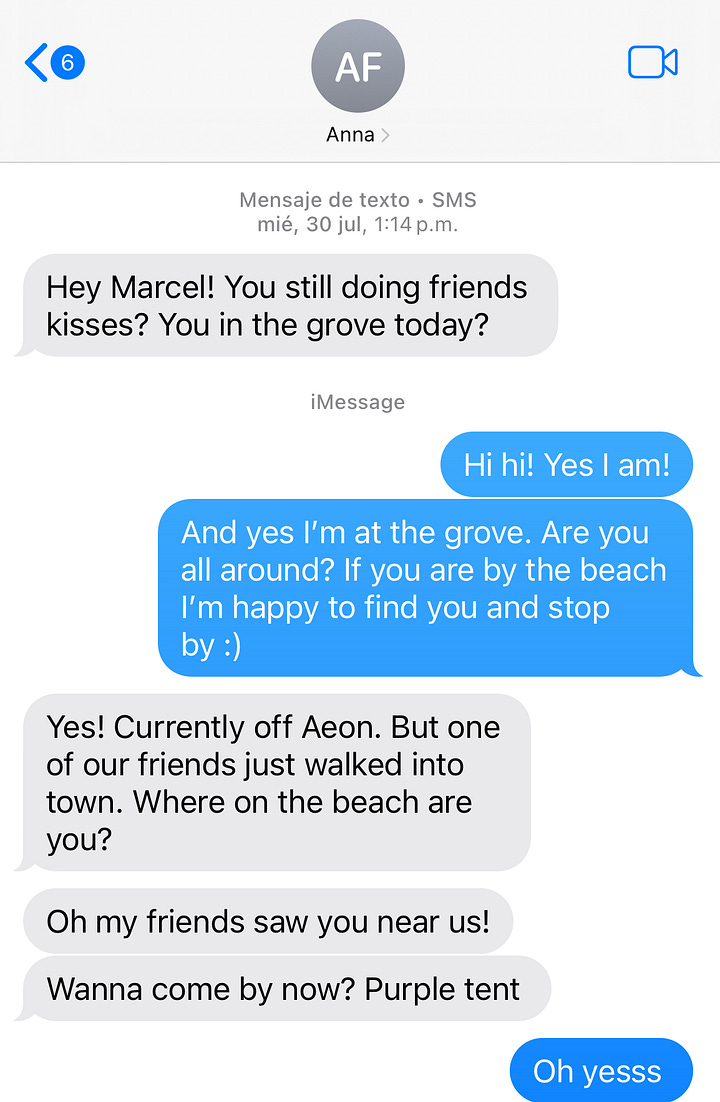

People texted me sweet messages like, “Hi Marcel, we are ready to kiss for you,” which definitely made me smile, or “Me and my friends are down to kiss.” I love the abstraction of bodies in the images, but I also love seeing people’s reactions after kissing their friends. People say things like, “Wow, that was so fun,” “We hadn’t done that before,” or, “Should we do it again, with tongue?”

I also spent a lot of time walking around the island, at least two hours a day. I kept feeling like there were so many queer spirits whispering and talking to me. It felt very special. There was a new kind of safety in wandering the paths at night, with no lights in sight, guided only by the white paint catching the glow of the moon. It was both profound and deeply peaceful.

How did your experience of growing up in Bogotá and later working across San Francisco inform your first impressions of Fire Island and the FIAR community?

My interest in queer history and archives had led me to learn about Fire Island many times. I was eager to go. I love the lineage of parties and resistance, and the Meat Rack as a place of desire, secrecy, and cruising. Yes, the island can feel very cis, and the energy was, without question, very white. But I also believe it’s essential for people of different positionalities to inhabit and shape that history, as well. We get to enjoy the magic of the island, too.

Growing up in a big city surrounded by mountains, the proximity to the ocean always feels like an enormous privilege. To step onto a beach that not only welcomes queerness but also celebrates the freedom of nude queer bodies was a rare and moving experience. I was aware that my brown trans body was uncommon in that landscape, yet I felt a quiet joy in claiming space there, letting the sand sift between my toes, noticing the salt on my skin, and listening to the sea, the trees, and birds as if they were telling me some chisme.

Were there books, queer artists, or local stories you encountered at FIAR that felt particularly resonant or transformative?

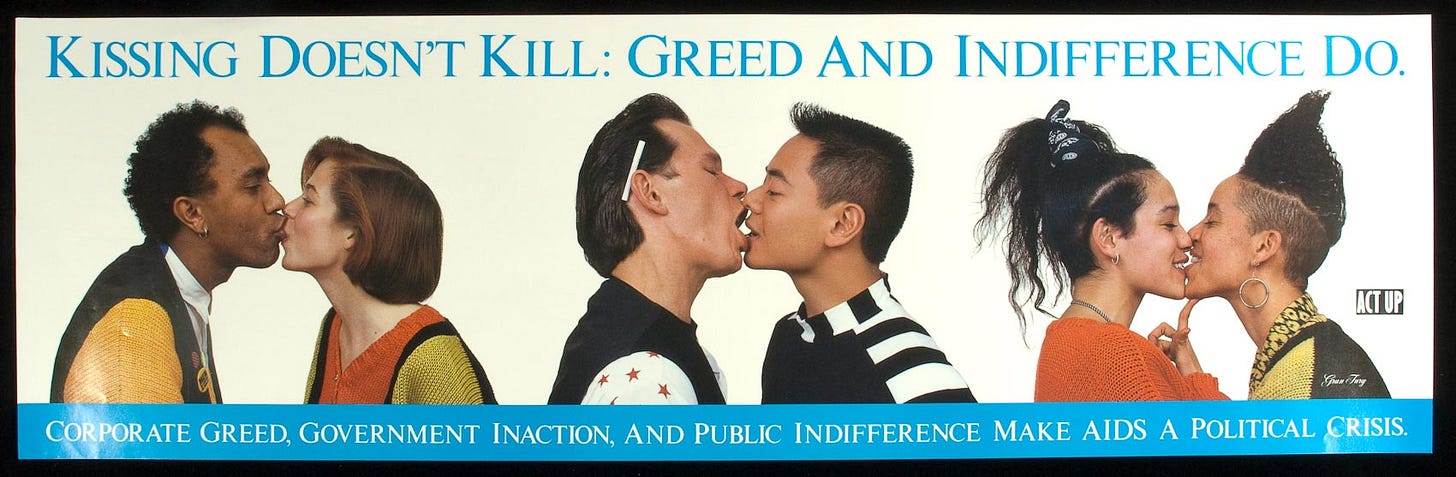

I met so many amazing people and had the chance to photograph over 70 people kissing, haha! But three moments stand out for me. Listening to the podcast “The Queer Grove” by filmmaker Parker Sargent while walking the island felt magical, as if the history were speaking directly to me. Cruising in the darkroom at the legendary Ice Palace underwear party was its own moment. And meeting photographer Lola Flash, whose work I’ve admired for years, was so special! I knew Lola had collaborated with my mentor Julie Tolentino on the Gran Fury Kissing Doesn’t Kill campaign, so it felt almost full-circle when Lola took a photograph of our FIAR cohort kissing. Queer art history in the making!!

Much of your work challenges the historical absence of trans Latinx narratives in visual culture. Did the residency spark new ways to imagine visibility in a place with such a loaded queer history?

Absolutely! I kept asking myself, How many trans masculine people from Colombia have been here? It felt important to create self-portraits that perhaps haven’t existed before on the island, to enter the visual history of the island with my brown trans body; it felt like the island itself was collaborating with me.

I’m also brainstorming ways to bring more queer, trans, Latinx, and immigrant folks to the island in a way that is both affordable and sustainable. The cost of visiting here can be prohibitive, which is one of the reasons the island is predominantly white. But I truly believe we need to carve out spaces for our people to enjoy this beautiful place, too. During my time there, I was able to invite people who’ve lived in NYC for years but had never visited the island before. It felt like a small but meaningful way to start breaking down those barriers and opening up the space for all of us.

Fire Island carries its own history, from gay liberation to coastal erasure to even white and classist at times. How did that layered context enter your practice during FIAR? You are now part of its history.

This happens in a lot of places, and I feel it very strongly in San Francisco, too. On Fire Island, there’s definitely a strong white cis male energy, but I also met people from a range of positions who are slowly making the island more inclusive. That work takes time and care, but as long as we recognize that this queer island is a paradise for rest and queer joy, we can remember that we deserve to be there too. Now, the challenge is finding ways to make it more accessible for others.

I think about the Fire Island Drag Invasion of 1976, when a group of drag queens sailed from Cherry Grove to the Pines to confront gender exclusion and binary gender norms. In a way, they transformed an act of defiance into a visual celebration of queer visibility. Or the more recent Doll Invasion, where trans, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming folks take over the island to reclaim a historically exclusive space and open it to our trans community. These creative interventions reimagine access and belonging to the island in really powerful ways that feel very inspiring. In the Pines, I took some kissing photos, but I knew I needed to push myself so the images didn’t feel repetitive. I still wish there had been more diverse moments, but in some ways, the work feels true to where the island is right now.

How does the temporary nature of residency communities inform your thoughts about building lasting connections?

This island has a deep sense of continuity; people have been living and coming here for decades, often returning the same weeks year after year. That creates a unique kind of community: transient yet consistent.

Consistency is one of the most important elements for building lasting connections. The fact that people have continued to care for the island’s history while enjoying it as a site of rest, joy, and desire feels pretty special. I know experiences of the island vary, but I personally felt embraced by it. I felt grateful for the freedom to, for example, proudly show my designer chest or feel mostly safe cruising in a predominantly gay male space. Of course, there’s still work to be done; I’d love to see more trans people on the island, and definitely more Black and brown folks, but I’m committed and hopeful that this will happen little by little.

Do you have a summer memory that comes to mind for this Summer 2025?

I have so many sweet memories of my time at FIAR! The beach slowed my mind to such a low level of stimulation that it felt like time itself stretched, something I hadn’t experienced in years. That spaciousness was a gift I now carry with me. I felt grounded, focused, and cared for by the ocean.

Beyond the magic of the beach, our FIAR cohort also had the chance to take two tours with the island’s gardener, Todd Erickson, one of the few year-round residents. He led us through the Meat Rack and the Sunken Forest, offering horticultural knowledge mixed in with so much tea. It felt particularly special to hear from someone who has lived on the island for so many years and tended to its flora with such care. Todd knows a great deal about different species, how they coexist, or don’t, and is deeply invested in the island’s long-term ecological health, especially in how visitors choose to conserve or neglect the place they come to enjoy.