Photos by Tori Mumtaz courtesy of The Shed

One recent Friday, I walked into Caffeine Underground, a large and unpretentious Bushwick coffee joint where, on any given day, I am far from the only trans person. I opened my laptop to find more “thanks, but no thanks” emails regarding my pitch to review “The Breakdown Odyssey,” trans rap artist Ms. Boogie’s one-night-only show on Saturday, September 14. None of the city’s top periodicals seemed to grasp the importance of the event, though it was the season opener at prominent Manhattan venue The Shed.

Boogie, a Dominican-Colombian native of East New York, has been a cultural force in the queer underground for more than a decade. She has toured the U.S. and Europe, produced polished music videos, and released three albums, the latest of which—“The Breakdown,” a storytelling opus backed by Brooklyn drill beats—was co-created by a team of queer and trans artists she flew across the country on her own dime.

I was bummed that I failed to sell my pitch about the show. Nonetheless, on a Saturday night, I took two trains and walked thirty minutes in three-inch heels to Hudson Yards, where I found Journey Streams, the 25-year-old art scene maven whose Yale dissertation on queer Brooklyn nightlife landed her a Verso Books deal. “This feels like a cross between The Whitney and LaGuardia Airport,” Streams laughed, gesturing around The Shed’s lobby.

In walked Byrell The Great, the preeminent DJ of New York City ballroom, who greeted Streams with air kisses before joining a gaggle of once and future ballroom legends at the lobby bar. Among them was Gia Love, the model and singer who founded an annual cookout to celebrate Black trans women, where Boogie performed last summer. (Boogie, too, first came up voguing in the ballroom scene.)

Doors opened, and ticket-holders rode three escalators along tall glass windows to the sixth floor of The Shed, where artistic director Alex Poots has said that he aims to “break down the barriers between so-called high and low culture.” In the venue’s black box Griffen Theater, three ornate crystal chandeliers glowed atop piles of rubble.

Boogie emerged in a nude, stocking-like bodysuit that revealed her dramatic curves while evoking the surgical contexts that shaped them. Over a droning soundscape by musical director M. Jamison, a trans woman who produced much of the album, Boogie crawled gollum-like from chandelier to chandelier, reciting broken-down verses from her album.

“Gotta do my due dills before I get killed,” she moaned breathlessly, reciting from the song “Black Butterfly,” a paean to the resilience of trans women of color living under constant threat of violence. “Quite frankly,” she intoned, “girls like me don’t grow tall like trees.”

The show was stunning as much for its content—a powerful trans woman brazenly baring her innermost struggles through poetry and physicality—as its form, which layered dance, performance, and fashion into a theatrical rap set. Boogie played various unnamed characters, her costume changes providing opportunities for singer Demi Vee, another Black trans woman, to bring the house down with heart-wrenching operatic singing.

In a Nike bodysuit and kneepads, Boogie crisscrossed the theater, slinkily accentuating her hips and flourishing her hands before squatting low and dipping to the floor. Abstract yet clearly voguing-inspired, the movements were co-choreographed by Alex Mugler, another ballroom success story. When Boogie performed “Aight Boom,” some in the crowd shouted every word: “Bitches got botched now they ask for my D-R / Your B.M. bad, but I’m bad-D-E-R.”

Boogie appeared alternately strong and vulnerable, breathing heavily then snapping back onto beat. Her next character wore a deconstructed gladiator skirt and knee-high black leather boots. Wavy black hair grazed her waist. She performed “Clipped,” a song processing a break-up, while Lambkin, the show’s movement assistant, played the role of a sympathetic hairdresser.

Boogie then sat beside a male figure wearing a hoodie, dramatically oversized jeans, untied Timberlands, and a grotesque, lacquered bull mask whose expression was perpetually dumbfounded. He personified DL trade, the kind of down-low men with whom Boogie, like many trans women, has extensive experience. I reached back to hold a friend’s hand, shuddering with recognition.

“Let me explain to you why you love me,” Boogie sang to the shame-ridden trade—touching empathy for an archetype who, to a trans woman, is at best, a passionate yet inconstant lover and, at worst, a threat to her life. The Beast would never give her the love she deserved, she conceded, but she was consoled by God’s love from above, which is “bigger and deeper than anything you can give me from below.” (She gestured to the Beast’s crotch.)

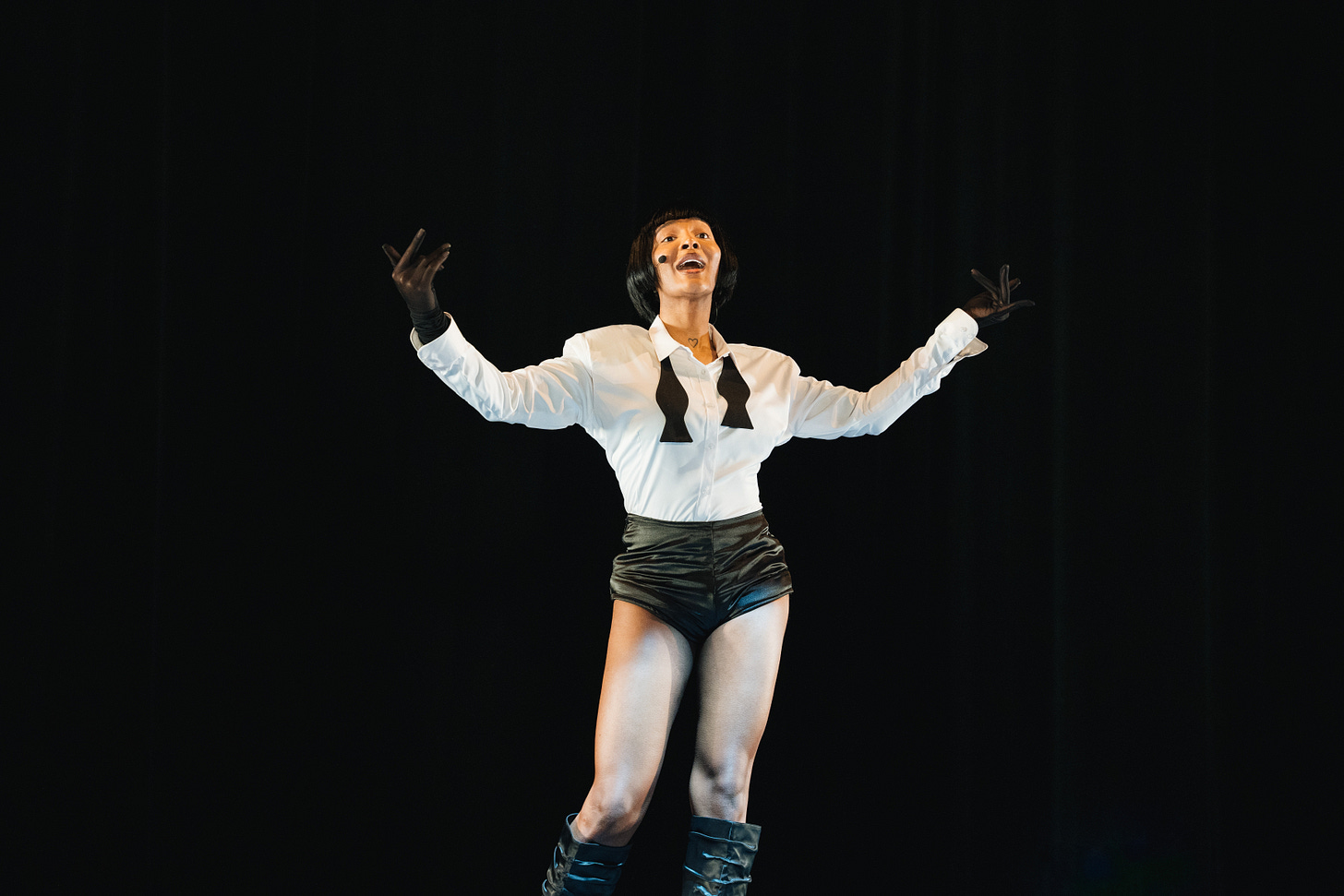

“I, too, am a child of God, contrary to popular belief,” Boogie proclaimed in a cheeky yet heartfelt closing monologue, channeling Broadway in the leotard version of a businessman’s undone suit. She pointed at the spotlights overhead and cried, “Thank Jesus I’m alive!” Then, blackout.

Immediately, I converged with two other white trans women in the audience. We were all just shy of speechless, having seen our own experiences so thoroughly depicted in a way they rarely are, certainly not with a budget. Yet we admitted we could only relate so much. Ms. Boogie’s perils are undoubtedly those of a trans woman who is Black; not a Bushwick transplant, but native to East New York.

Still, Boogie’s relentlessly honest and innovative performance impassioned me. I felt called to tell my own story, which is unique yet partakes of the odyssey on which every trans woman embarks. What I had just witnessed was a masterpiece, and I felt livid that the cis establishment couldn’t see that, or at least wouldn’t give it space in their periodicals. But Boogie reminded me of the power in working with those in your own community, the ones who get it. So I took the story elsewhere.